What Does Cancer Grade Mean?

By: David Grew MD MPH

Cancer grade and stage are distinct but significant factors in cancer care.

∗ ∗ ∗

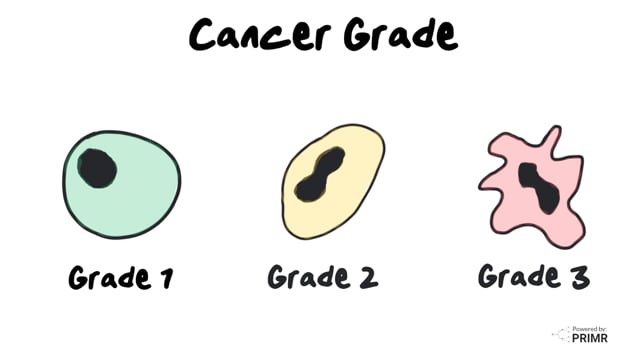

Cancer grade is a measure of how aggressive a cancer appears under a microscope. But that is just the beginning of the story.

Cancer grade is often confused with cancer stage, which is a measure of how far a cancer has spread, or how advanced it is. While the terms may sound interchangeable at first pass, grade and stage are not always correlated. We often see early stage cancers that are high grade, and likewise low grade cancers can grow and spread to advanced stages.

Our bodies are made of of small units called cells. There are skin cells and breast cells and prostate cells and bone cells and lung cells. Cancers can grow from any cell in the body. The more genetic mutations they accumulate, the more aggressive they behave, the less they look like the original cell from which they grew. So doctors use the appearance of cancer cells as a proxy measure of how aggressive they might behave, grow and spread throughout the body. Doctors sometimes use this information to either ratchet up or dial back treatment intensity to match the expected behavior of cancer.

In this blog we’ll review what each grade typically means, and how it might affect treatment, with some specific examples from common cancers.

What is grade 1 cancer?

Grade 1 cancer is the least aggressive of all the grades. It may also be called “low grade” cancer, or “well differentiated”. When doctors inspect grade 1 cancer under a microscope - either after a biopsy or after surgery - they see cancer cells that look relatively similar to the cell type from which they arose. Generally, grade 1 cancers have acquired fewer mutations compared to high grade (grade 3) cancer and behave less aggressively.

This is important because it gives doctors some reassurance that this cancer is less likely to grow back after basic treatments like surgery. In some cases, low grade cancers are so slow growing, sometimes called “indolent”, they can actually just be watched closely with no active treatment at all. An example of this approach is active surveillance in prostate cancer. (We made a video about a clinical trial for prostate cancer patients interested in active surveillance.)

Examples of grade 1 cancers that may be candidates for less treatments include small breast cancers that have been completely removed with negative margins (especially elderly patients), early stage endometrial or uterine cancers, and certain sarcomas and skin cancers that are surgically removed. A step further, low grade (Gleason 3+3=6 or grade group 1) prostate cancer is a common example of low grade cancer that can avoid treatment altogether so long as the PSA is low and the cancer has not spread.

What is grade 2 cancer?

Grade 2 cancer, also known as intermediate grade, is not the least aggressive, and not the most aggressive - it’s in the middle. Under the microscope they appear to have some features doctors can see that portent slightly more aggressive behavior than grade 1.

When doctors see grade 2 (instead of grade 1), they may be less comfortable skipping treatment. This is because since grade 2 tumors behave more aggressively, they may grow in between follow up visits when doctors are monitoring for growth, potentially missing a chance at curative treatment.

What is grade 3 cancer?

Grade 3 cancer is the most aggressive grade. It may also be called “high grade” or “poorly differentiated”. When doctors look at grade 3 cancer under the microscope, they see cancer cells that look very different compared to the cell type from which they arose. This is because they have acquired so many mutations that they start to take on odd shapes. In addition, they grow fast, so under the microscope we can see many cancer cells replicating and dividing (essentially growing) into new cancer cells.

Usually, patients with grade 3 cancer are not good candidates for active surveillance or de-escalation of therapy. Examples of this include breast cancer and prostate cancer. In most cases patients with grade 3 breast cancer receive radiation treatment after lumpectomy (where for certain grade 1 tumors you may skip radiation with a reasonably low chance of recurrence). Patients with high grade (grade group 3, 4 or 5) prostate cancer are usually not candidates for active surveillance. Other factors that may affect a doctor’s recommendations on this include both patient factors (age, other medical issues) and other cancer factors (stage, surgical margin status, size, hormone receptor status, genomic testing results).

As always - this is for educational purposes only. This is not medical advice. Talk to your doctor before making any medical decisions.

FAQs:

Are there any emerging technologies or advancements in cancer grading systems that aim to improve the accuracy and consistency of grade classification across different types of cancer?

Yes. These advancements often involve integrating molecular and genetic analyses alongside traditional microscopic examination to provide a more comprehensive understanding of tumor behavior and aggressiveness. Techniques such as genomic profiling and digital pathology are among the innovative approaches that aim to refine cancer grading and improve treatment decision-making.

Can cancer grade change over time, either spontaneously or in response to treatment, and if so, how does this affect treatment planning and prognosis?

Absolutely. This can happen either spontaneously or in response to treatment. This phenomenon, known as tumor evolution, can result from genetic mutations, environmental factors, or therapeutic interventions. Changes in cancer grade may impact treatment planning and prognosis by influencing the aggressiveness of the disease and the responsiveness to specific therapies. For example, an increase in cancer grade may prompt a shift to more intensive treatments, while a decrease in grade could indicate a favorable response to therapy and guide decisions regarding treatment continuation or modification.

Are there instances where the grade of cancer cells does not align with the aggressiveness of the disease, leading to discrepancies in treatment recommendations or outcomes?

Unfortunately, this discrepancy can occur due to various factors, including tumor heterogeneity, wherein different regions of the tumor exhibit varying grades of aggressiveness. Additionally, advancements in molecular profiling have revealed that some tumors with low-grade morphology may harbor genetic alterations associated with more aggressive behavior, challenging conventional grading systems. As a result, personalized approaches to cancer management, incorporating molecular markers and comprehensive tumor characterization, are increasingly recognized as essential for optimizing treatment decisions and improving patient outcomes.

Other Posts

The Untapped Potential of a Century-Old Treatment: Reviving Low-Dose Radiation Therapy for Osteoarthritis

Navigating the Evolving Landscape of Informed Consent in Clinical Trials: Draft FDA Guidance and the PRIMR Approach